- Abstract

- Introduction

- Overview performances of fdi determinants in

arabophones and francophone economy - Literature review

- Methodology

- Empirical results and

interpretations - Conclusion

- References

Abstract

This paper undertook a comparative static analysis of

foreign direct investment (FDI) determinants on FDI inflows to

Arabophones and Francophones countries in Africa. This paper used

an unbalanced panel data on non-landlocked Africa member states

excluding the Lusophone member states from 1980 to 2010. To

accomplish this, Panel unit root test, Pedroni (Engle-Granger

Based) Panel Co-integration Test, multi-collearity test and

Hausman test were conducted before using a panel dynamic ordinary

least square estimation under the fixed effect specification for

the entire models. Contemporaneous trade openness, financial

development, economic growth and short- term investment in

infrastructural was positive determinants of FDI inflows to

non-landlocked Africa countries excluding the Lusophone Africa.

On the contrary, lagged of infrastructure development, lead of

domestic savings and balance of payment was identified as part of

FDI determinants to Arabophones member states, even though the

effects were negative. Nevertheless, the result showed that

language is not a significant factor for attracting FDI inflows.

Finally, policies/strategies to improve the economic growth and

trade openness should be put in place in order to attract more

FDI inflows to non-landlocked Africa.

Key words: Foreign direct investment,

non-landlocked, Arobophones and Francophones.

Introduction

Developing countries are ever more informed on the

significant role of foreign direct investment

(FDI[1]as an engine of growth in their economies.

Theories have elicited that FDI can induce economic growth by

providing essential capital and skills, participating in large

projects and as well as being a vehicle for technology transfer.

For many developing countries, FDI has been an essential

mechanism that promotes industries, entailed the spirit of

competition and in the long-run makes them have a potential

comparative advantage over other economies (Addison et

al, 2004; UNCTAD, 2003; Dunning & Hamdani,

1997).

Literatures have identified many determinants of FDI in

an economy. These determinants effects differ from one economy or

region to another. According to Calvo et al. (1993)

study argued that, the total FDI inflows in a country are stirred

largely by push factors, such as economic growth and return on

investment in industrial countries. That is, the foreign

investors" main objective is profit maximization. The implication

is that investors will move to a new destination if the return on

investment in that destination is promising. Apart from the FDI

determinants associated with push factors, there are other

determinants of FDI which are linked to pull factors. According

to Collins (2002), the Pull factors enabled the investors to

choose a profitable investment allocation among developing

countries.

In addition to pull and push factors, foreign direct

investor"s reason of investing in a particular economy might be

related to their motives. For example, a natural-resource-seeking

investor aims to exploit the natural resource endowments of that

country. This investor will mostly channel funds to companies

extracting oil (in Nigeria, and Cote d"Ivoire), gold (in Ghana)

and diamond (in Botswana), etc. Other types of investor are:

Market-seeking investors who aim at taking advantage of new

markets in terms of their sizes and/or growths.

Efficiency-seeking investors take advantage of special features

such as the costs of labor, the skills of the labor force, and

the quality and efficiency of infrastructure. Lastly,

strategic-asset-seeking FDI investors situate at a place where

they can take advantage of what is readily available in terms of

research and development and other benefits.

Based on the empirical and theoretical identification of

various FDI determinants work covering a wider range of countries

and its effect on FDI to recipient economy, which might depend

not only on local conditions and policies but also the linguistic

approach cognition. Simply put, one question this paper

postulated was whether the disparities in terms of language were

a factor in attracting FDI inflows to Northern Africa. That is,

whether the official language was a latent determinant

instrumented for the economy in question to harvest benefits

derived from FDI inflows.

In this paper, the author explores a comparative static

analysis of FDI determinants effect on FDI inflows to Arabophones

and Francophones countries in Africa. In order to do this, the

author sourced data from UNCTAD"s and Africa Development

indicator database. In total, the sample covered 12 African

countries, among which five of were Arabophones countries,

namely, Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and Mauritania while the

rest, Gabon, Benin, Guinea, Madagascar, Senegal and Côte

d'Ivoire belonged to Francophones countries. The paper adopted a

dynamic ordinary least square (DOLS) method to achieve its entire

objectives. The rest of the paper was organized as follows,

Section two contained a comparative static analysis overview

performances of FDI determinants in Arabophones and Francophone

economy, while section three reviewed the theoretical and

empirical literature from other related studies, from which the

paper derive determinants of FDI having a potential impact on FDI

inflows Arabophones and Francophones countries. The methodology,

econometric specification and estimation strategy were presented

in section four. Empirical results and their interpretations were

discussed in section five, while section six summarized, and

present policy discussion and made suggestions for further

research.

Overview

performances of fdi determinants in arabophones and francophone

economy

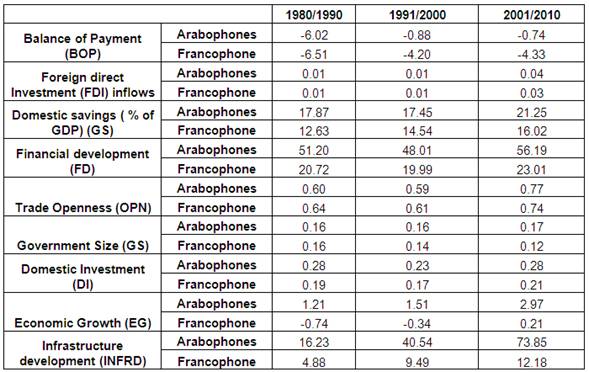

Table1: Comparative Static Analysis

Sources: UNCTAD and WDI and the

calculation were done by the author.

In table 1, both the Arabophones and Francophones member

states on average were running balance of payment deficits from

over the period of this empirical study. For example, between

1980 and 1990, the BOP deficits for Arabophones and Francophones

were 6.02 percent and 6.51 percent of their gross domestic

product respectively. But the deficit on average reduced to 0.88

percent between 1991 and 2000 and further to 0.74 percent from

2001 and 2010 for Arabophones member states economy. There were

reductions on average in Francophone countries within the same

periods but not as compared with Arabophones

countries.

In both Arabophones and Francophone member states, their

domestic savings increase but Arabophones domestic savings

increases more than Francophone over the same periods. The

financial development (FD) in Arabophones, were more than twice

liberalized than in Francophone member states. For instance, it

was 51.20 percent and 20.72 percent for Arabophones and

Francophones in 1980-1990 respectively. The development of the

financial system dropped a bit for both member states in

1991-2000 and picked up to 56.19 percent and 23.01 percent in

2001-2010 for Arabophones and Francophones

respectively.

Furthermore, there is fairly level of trade openness for

both Arabophones and Francophones member states, but Francophones

countries were more open than Arabophones countries in 1980-1990

and 1991-2010. This is an evidence of adopting globalization in

their various economies. The government participation in both

member states were low and fairly stable in both economies.

Domestic investments in Arabophones countries were slightly

higher when compared to Francophones countries. Finally, the FDI

inflows in both countries were approximately the same over three

deciles observation.

In figure 1 below, FDI inflows in Arabophones were

increased from 1980 to 1994, and dropped from 1994-1995 while

over the same period FDI inflows to Francophones countries were

fairly stable. The FDI inflows for both member states were

increased from 2004 to 2006, and Arabophones attracts more than

Francophones member states. From 2006 to 2008, FDI inflows to

Arabophones countries were approximately stable but the increase

of FDI inflows continued flowing to Francophones countries over

the same period. Finally, after 2008, the FDI inflows to

Arabophones declined.

Figure 1: FDI inflows in Arabophones and

Francophone"s countries in Africa (1980-2010)

Source: Africa development Indicators

various years

Literature

review

3.1 Reviews of Theoretical Literature

There are a number of theories that have explained

Foreign Direct Investment inflows (FDI) in Africa. FDI theories

are mainly based on imperfect market conditions and imperfect

capital market. Some of these theories consider the effect of

non-economic factors on FDI while others explain the emergence of

Multinational Corporations (MNCs) exclusively among developing

countries. For instance, neo-classical economic theory assumes a

free capital markets and diminishing returns. According to the

theory, capital should flow from capital abundant countries

(developed countries) to capital scarce countries (developing

countries) until the marginal returns to capital in both

countries are equal. Such flows can contribute immensely to

closing domestic savings gap in developing countries (Page &

Velde, 2004). Indeed, Mundell"s (1957) in the Heckscher-Ohlin

theory of trade postulated that capital will move from rich

countries to poor countries. The implication is that, it is more

profitable to invest capital where it is scarce than where it is

abundant. It holds on the assumption that there should be no

outflows of FDI from developing countries.

In addition, FDI is associated to production as well as

capital flows, which are influenced by other factors. From a

conventional trade point of view, trade and FDI might be viewed

as substitutes in absence of the influence of factors such as

technology and firm-specific assets; otherwise they may be seen

as complements (Markusen, 1984 & 1995). A notable example of

firm-specific assets is brand names which are acquired via

advertising or firm specific knowledge acquired via Research and

Development (R&D).

Nevertheless, there are other factors that influence FDI

inflows in a particular country other than differences in factor

endowments and factor prices. Trade economists believe that

return on investment, imperfect competition and product

differentiation and other factors related to the comparative

advantage paradigm are part of FDI investor"s motive. Apart from

trade theory, Dunning"s eclectic paradigm explained in detail

some important variables essential in attracting FDI inflows to

Africa.

Dunning"s eclectic paradigm which is the combination of

the imperfect market-based theories of FDI, that is, industrial

organization theory, internalization theory and location theory.

It postulates that, at any given time, the stock of foreign

assets owned by a multinational firm is determined by a

combination of firm specific or ownership advantage, the extent

of location bound endowments, and the extent to which these

advantages are marketed within the various units of the firm. The

theory further argued that, the reason why FDI inflows are

greater in one country but not in another is the country"s

locational advantage. (Dunning, 1980, 1993). Dunning identifies

four major types of FDI investors and their associated motives

which are; market-seeking foreign investors will move to a

country with less openness, efficiency- seeking foreign investors

will move to a country with low labor cost, while natural

resource-seeking foreign investors will invest on a country that

is endowed with natural resources and strategic asset seeking

investors flows to a country that is advanced in technology,

skills or take over brand names.

Based on the foreign direct investment theories reviewed

so far, it is improper to accept any of the above theories to

explain the effect of some selected determinants of foreign

direct investment inflows on Arabophones and Francophone"s

countries. This is because the above theories was not able to

combine both the investors" motives related factors and that of

the host countries related factors detrimental to foreign direct

investment inflows. For this reason, the current paper adopted

the integrative theory.

The integrative theory gives a clearer view of the

effects of some determinants of FDI inflows by analyzing it from

the perspectives of host countries as well as investors. It

incorporated the effect of the short-run, contemporaneous and the

long-run effect of the FDI determinants on FDI inflows into its

theory. For instance, eclectic paradigm, which is the combination

of the firm and internalization theories, and industrial

organization theory tackle FDI determinants from the viewpoint of

the firm. The neoclassical and perfect market theories examine

FDI from the perspective of free trade. The development and

dependency theories shed light on the perspective of the host

nation while integrative theory integrates those neoclassical,

developments, dependency and eclectic paradigm that are important

in attracting FDI inflows into a country in its

theory.

According to integrative theory, foreign direct inflows

are a function of the host country factors, the firms" factors

and the foreign direct investors" related factors. Integrative

theories account for the multiplicity of heterogeneous variables

involved in attracting the FDI inflows in Africa. It also forms

the current study theoretical background for identifying

determinants of foreign direct investment using linguistic

approach for comparative static analysis. Integrative theory is

presented as;

FDI inflows = F (factors related to the host

country, firm specific factors and investor factors related to

their motives).

The interactive theoretical framework gives the basis

for adopting dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) model of the

current study to identify determinants of foreign direct

investment in Arabophones and Francophone"s countries in Africa.

The model captured all the relevant factors identified by

interactive theory.

3.2 Reviews of Empirical studies

There are a number of empirical studies that have shown

the effect of determinants of FDI in attracting it to the host

countries. FDI has empirically been found to stimulate economic

growth by a number of researchers (Glass & Saggi, 1999). It

was also true according to Dees (1998) that China"s economic

growth is an evidence of FDI spillovers. In Latin America FDI

inflows has contributed a lot to the economic development of

selected Latin America economy (De Mello, 1997). Some other

studies conducted in the same region found that a certain income

level is a crucial determinant of FDI inflows; below that level

it does not have any effect (Blomstrom et al., 1994,

Bengos & Sanchez-Robles, 2003). Their explanation was that a

host country should have the capacity to absorb the effect of FDI

inflows otherwise it would have no effect on the host country"s

economy.

Neoclassical economists have argued that FDI influences

economic growth by increasing the amount of capital per person.

It does not influence long-run economic growth due to diminishing

returns to capital. A study conducted in East Asia has shown that

FDI has a positive effect on less advanced economy"s output than

advanced economy (Bende-Nanende et al. 2002). However,

there was no consensus on the positive impact of FDI on growth.

For instance, a study conducted by Globeram (1979) on some

selected developing countries stipulated that FDI has a

significant effect on economic growth of the countries studied

via its positive effect on domestic firms. Eighteen years later,

Regnanet (1997) conducted a study in the same countries which he

found the same result as Globeram. On the contrary, a study

conducted in Asia countries by Aitken et al. (1997)

found a negative relationship between FDI and economic growth.

Other found inconclusive result. Zhang (2001) emphasizes that the

effect of FDI has on the growth or growth of FDI of any economy

may be country and period specific. Another determinant of FDI is

financial development.

Financial Development stimulates the growth process of

an economy. Its indicators assess the size, activities, and

efficiency of a financial intermediaries and market in a country

(Beck, Demirguc-Kunt & Levine, 2000). Financial development

can make it easier for aid recipient countries to assess aid from

foreign aid donors (Nkusu and Sayek, 2004). Furthermore, Beck"s

study shows that countries with an effective financial sector

have a comparative advantage in manufacturing industries.

Nabamita and Sanjukwa (2008) agreed with Beck and highlighted the

functions of financial development as the following; channeling

resources efficiently, mobilizing savings, reducing the

information asymmetry problem, facilitating trading, hedging,

pooling and diversification of risk, aiding the exchange of goods

and services and monitoring managers by exerting corporate

control. Hermes and Lensink (2003) argued that financial

development has a positive effect on FDI. The reasons advanced

for the result were; a developed financial system mobilizes

savings efficiently and as such may increase the amount of

resources available to undertake investment. A well developed

financial system reduces financial transaction and information

acquisition costs. Financial development also speeds up the

adoption of new technologies by minimizing the risk associated

with it. With a well developed financial system, foreign

investors are able to deduce how much they can borrow for

innovative activities and are able to make investment financing

decision ahead of time. It also increases liquidity and, thus,

facilitates trading of financial instruments and timing and

settlement of such trades (Levine, 1997). This will also lead to

greater FDI inflows as the projects can be undertaken with lesser

time being spent in settling the trades. Nabamita and Sanjukta

(2008) conducted a study on developing countries and their

findings were that there was a positive relationship between

financial development and FDI inflows after a threshold level of

financial development is reached. Beyond that level the effect

becomes negative.

In theory, openness is one of the determinants of FDI

inflows. Its effect on FDI inflows to an economy differs based on

the investor"s motivation for engaging in FDI activities

(Brainard, 1997; Markusen & Maskus, 2002; Navaretti and

Venables, 2004). The more open an economy becomes the better for

non-market seeking investors who would like to use the

destination as an export base. On the contrary, market seeking

investor who"s their target market is the host countries would

prefer less openness. There are vast numbers of empirical studies

that have found openness as an important determinant of FDI

inflows. Chakrabarti (2001) study on the determinants of FDI

inflows to developing countries, the study found out that

openness is an important determinant of FDI and is positively

related to FDI inflows. Moosa and Cardak (2006) conducted a

similar study as Chakrabarti"s, they discovered that export as a

percentage of GDP positively affects FDI inflows. Openness is

found to be positively and significantly related to FDI inflows

in developing countries (Lucas, 1993, Singh & Jun 1995). On

the contrary, Busse & Hefeker (2007) and Globerman and

Shapiro (2002), concluded that openness is statistically

insignificant and does not affect FDI inflows. Some other

researchers found an inclusive result with respect to FDI, such

as Goodspeed et al. (2006). They found a positive and

significant relation with FDI inflows in one model and

insignificant in other specifications of the empirical model.

When testing the vertical, horizontal and knowledge capital

models, Markusen and Maskus (2002) concluded that trade precincts

might be less significant as a motivation for horizontal

tariff-jumping investments in developing countries. This means

that a greater degree of openness will have less of an effect on

the market-seeking investments in developing countries in

comparison to developed countries.

Asiedu (2002) conducted a study by selecting some

African countries; the author"s result implied that openness on

FDI has a lesser effect in Sub-Saharan Africa when compared to

other developing countries. Contrary to Asideu, Tøndel

(2008) found that openness has a higher influence of FDI inflows

in Sub-Saharan Africa than for other countries. There is also

some evidence with respect to differences within the group of

transition countries. When the economies first opened up for

foreign participation in the 1990s, investments in Central Europe

were vertical, whereas FDI activities in the Commonwealth of

Independent States were either market or resource-seeking (Lankes

& Venables, 1998; Meyer, 1998).

Morisset (2000) used panel data of 29 African countries

over the period 1990-1997 to study the main determinants of FDI

in Africa. Morisset"s study stipulated that GDP growth rate and

openness are positively related to FDI in Africa. Campos and

Kinoshita (2003) used panel data of 25 transition economies from

1990-1998 to study the main determinants of FDI. They found that

natural resource endowment is the main determinant of FDI flows

in Africa.

Return on investment is a critical factor for rational

investors. Foreign direct investors will go to countries that pay

a higher return on capital. According to Asiedu (2001), measuring

the rate of return in developing countries is a difficult

process. The reason is that the capital market in developing

countries is under develop. The measurement which has been

adopted for this variable is to use the inverse of real GDP per

capita to measure the return on capital. The empirical result of

the relationship between real GDP per capita and FDI is diverse.

Edwards (1990) and Jaspersen et al. (2000) used the inverse of

income per capita as a proxy for the return on capital and they

concluded that real GDP per capita and FDI inflows as a ratio of

GDP are negatively related. Schneider and Frey (1985) and Tsai

(1994) studies found a positive relationship between the two

variables. This is based on the argument that a higher GDP per

capita implies better prospects for FDI in the host

country.

One of the ways in which FDI positively affects economic

growth is through the release of binding constraint on domestic

savings in the economy. FDI makes it through the process of

Capital accumulation. Given that domestic savings in Africa are

very low, which may result in a low investment rate and hence

lead to sluggish economic development (Ajayi, 2006). A study

conducted by Khan & Bamou (2006) on some selected developing

countries. They found that FDI has a positive effect on domestic

savings through foreign savings. Other studies also found results

that are consistent with those of Khan and Bamou (Asante, 2006,

Abedian, 2003). Less emphasize has been put on trying to see

effect of an improving domestic savings on FDI.

3.3 Conclusion

The literature findings have shown the great importance

of FDI in Africa. It has also highlighted that Africa needs

economic development, which is evidenced in the performance of

some macroeconomic indicators identified by the literature and

empirical studies. There has been an inconclusive finding on the

effect of some determinants of FDI on attracting FDI inflows to a

country, and few papers have undertaken a comparative study using

a linguistic approach. However, this paper has contributed to the

plethora of literature by adopting a linguistic approach to

identify the effect of some determinants of FDI inflows in

Arabophones and Francophones" countries.

Methodology

4.1 Types and sources of data

Secondary annual data were used in the study. The data

were sourced from the United Nations Conference on Trade and

Development (UNCTAD) data base and World Bank Development

indicators (WDI) database. The period considered for the study

was 1980-2010.

4.2 Model specification

The paper used the following variables in the model

specification to assess the effect of economic growth (EG),

inflation (INF), financial development (FD), openness (OPN),

balance of payments (BOP), domestic savings (DS), infrastructure

development (INFRD), government size (GS), return on investment

(RI), domestic investment (DI), and country specific dummies on

Foreign Direct Investment inflows in Arabophones and Francophone

non-landlocked Africa countries.

Table 2: Description of variables

Variables | Measurement | Data Source | Expected effect on | ||||

FDI | FDI inflows as a ratio of | UNCTAD | – | ||||

EG | Real GDP growth per | UNCTAD | Positive | ||||

FD | M2/GDP | World bank development indicator | Positive | ||||

INF | Inflation, consumer price | WDI | Negative | ||||

OPN | (export +import)/GDP | UNCTAD, author | ambiguous | ||||

DS | Gross domestic saving as % of | WDI | Positive | ||||

RI | Inverse of real GDP growth per | UNCTAD, but author | Positive | ||||

GS | Ratio of government consumption to | UNCTAD | ambiguous | ||||

INFRD | Ratio of number of telephone lines | WDI | Positive | ||||

DI | Gross capital formation to | UNCTAD, author | ambiguous | ||||

BOP | Balance of payment as % of | WDI | Negative | ||||

Dummies | DumArab and DumFranc | Authors calculation | positive | ||||

The dynamic ordinary least square estimates for

heterogeneous panel

4.3 Techniques for data analysis

The paper first tests for Stationarity of the variables

included in the models. The variables that are non-stationary at

level were not tested for the existence of a co-integrating

relationship because the dependent variable (FDI inflows) was

stationary at level. Multi-Co linearity check was conducted using

correlation matrix. The paper also had undergone some diagnostic

tests such as Wald- test and Hausman test. Before estimating

panel DOLS, the Hausman test preferred a fixed specification to

random effects. The next step was to use a Dynamic ordinary least

square (DOLS) regression to estimate the effect of some FDI

determinants on FDI inflows in Arabophones and Francophone"s

countries on a comparative static analysis.

Empirical results

and interpretations

5.1 Panel Unit Root Test

The panel unit root tests were carried out to test for

the Stationarity of the variables used in the model

specification. The tests are necessary in order to avoid spurious

results. This study adopted two types of first

generation[2]panel unit root test such as Levin,

Lin and Chu (LLC) (2002) and Fisher-Type test using Augmented

Dickey Fuller ADF (Maddala and Wu, (1999)). The reasons why the

study has chosen LLC and ADF over Im, Pesaran and Shin (IPS)

(2003) and others is that; LLC generalize the Quah"s model which

allows for heterogeneity of individual deterministic effects

(constant and/or linear time trend) and heterogeneous serial

correlation structure of the error terms assuming homogeneous

first order autoregressive parameters. They assume that both

N and T tend to infinity but T

increase at a faster rate, such that N/T

approaches to zero. ADF is similar to IPS but both LLC and

Fisher- ADF allows for an unbalanced data in the test while IPS

does not allow for unbalanced data. Therefore, the tests are

suitable for this paper because its analysis was based on

unbalanced data specifications.

Levin, Lin and Chu (2002) as well as ADF- Fisher

Chi-square were proposed by Madala and Wu (1999) and they both

have the same null hypothesis of unit root is presence against

its alternatives.

In table 3 below, eight variables out of the eleven

variables used in this paper were stationary at levels including

the dependent variable FDI. Although the rest of the variables

were stationary after first differencing, the co – integration

test was not conducted because the dependent variables were

stationary at level. The two adopted tests such as an LLC and

ADF-fishers chi-square were consistent with their inferences. The

variables with asterisk indicated the Stationarity integral

order.

Table 3: Panel Unit

root[3]for Non-landlocked Africa

Countries

Probabilities are computed assuming

asymptotic normality. Critical values 1% * 5%**and Critical

values at 10%*** ASL represented Already Stationary at

Level

In table 4, Stationarity test was conducted by dividing

the non-locked countries into Arabophones and Francophone

countries in Africa. The table shows that four variables out of

the eleven variables were stationary at levels including the

dependent variable (FDI) and the rest became stationary after

first differencing using ADF-Fishers Chi-square test. The result

was partly consistent with intercept only and intercept and trend

specification. The inconsistency was that two additional

variables became stationary at levels with intercept and trend in

Arabophones. These included the dependent variable and trade

openness (OPN). In the Francophone specification, seven variables

out of the eleven variables became stationary at levels excluding

the dependent variables when included only intercept. The nature

of the variables showed the same results when intercept and trend

were included, although it differs with domestic investment

(DI).

Table 4: Panel Unit root for Comparative

analysis using ADF-Fishers Chi-square

Probabilities are computed assuming

asymptotic normality. Critical values 1% * 5%**and Critical

values at 10%*** ASL represented Already Stationary at Level. The

value in () represented variable that became stationary after

differencing and it is exclusively for stationary

test.

Although that the dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS)

model adopted included the long run and short run effect but in

the advert of non-significant lags and lead variable the long run

relationship disappears. Therefore, panel Co-integration became a

necessary test for Arabophones and Francophone models.

5.2 Panel Co-integration

Test

This paper employed Pedroni (Engle-Ganger based) Panel

co-integration test suggested by Pedroni (1995, 1999, 2000).

These tests extend the Engle and Granger (1987) two-step strategy

to panels and relied on the ADF and PP principles.

Pedroni (1995, 1999, and 2000) proposed seven test

statistics for co-integration in a panel framework. Four of the

statistics are called panel co-integration statistics, which

pooled within-dimension based statistics (Pedroni, 1995, 1999).

The other three statistics developed by Pedroni (2000), are

called Group-mean Panel Co-integration statistics, which are

between-dimension panel statistics. The seven statistic is given

as:

Each of the panel test statistics will be distributed

asymptotically as a normal distribution.

The null hypothesis of no co-integration against the

alternative of co-integration was tested using the seven

statistics. According to the test if more than half of statistic

were statistical significant, then the null hypothesis of no

co-integration is rejected, otherwise you fail to reject the null

co-integration.

Table 5: Pedroni (Engle-Granger Based) Panel

Co-integration Test

Probabilities are computed assuming asymptotic

normality. Critical values 1% * 5%**and Critical values at 10%***

represents the level of significance of the

statistic.

In table 5, the co-integration model for Francophones

countries includes; Foreign Direct Investment, trade openness,

infrastructure development and financial development variables.

The co-integration model for Arabophones countries includes

foreign direct investment, trade openness, inflation, domestic

investment, financial development and balance of payment.

According to the test, there was a long run relationship between

the independent variables and foreign direct investment in both

model specifications. The variables included in the

Co-integration test were those variables which became stationary

after first differencing.

5.3: Model specification

test

Table 6: Correlation

Matrix[4]

The values without a bracket, [ ] and (

) denotes the correlation matrices for non-landlocked Africa,

Arabophones and Francophones countries

respectively.

Table 6 shows the correlation matrices of different

variables in the three models. This is one way of testing the

presence of multicollinearity in model estimation. According to

the test, none of the independent variable is highly correlated

to each other. The next specification test conducted by this

paper was Hausman test.

Table 7: Correlated Random effects-Hausman

test[5]

According to table 6, the proper model specification for

all the models was under fixed effect estimation which the paper

adopted.

5.4 Empirical Results and Discussions

This paper used Dynamic Ordinary Least Square (DOLS) to

answer all the objectives. The DOLS allowed for the inclusion of

both variables that were stationary at levels and those that

became stationary after differencing in the model. The lag and

lead of explanatory variables that were not stationary at level

were included in the model after differencing and insignificant

lag and lead variables were excluded in the final presentation of

the tables below.

Table 8 below shows empirical findings of the

determinants of FDI on FDI inflows in Arabophones, Francophone

and non-landlocked Africa countries. The non-landlocked countries

exclusively include only those countries that their official

language is either French in the case of Francophone or Arabic

for Arabophones. The model included in its panel estimation,

seven Francophone countries such as Gabon, Benin, Cote d"Ivoire,

Togo, Guinea, Madagascar, and Senegal.

Table 8: Linguistic approach effect of

FDI determinants in non-landlocked Africa

countries

Probabilities are computed assuming

asymptotic normality.

The five Arabophones countries included in the analysis

were Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, and Mauritania. The

variables included in the model were Investment (DI), Domestic

Savings (DS), Economic Growth (EG), Inflation (INF), and

Infrastructure Development (INFRD), Government Size (GS),

Openness (OPN), Balance of Payment (BOP), Financial Development

(FD), and Return on Investment. Durbin-Watson statistic of 1.709,

1.051, 0.977, 0.978 and 0.978 as in Arabophones, Francophone,

non-landlocked, inclusion of Arab dummy, and the inclusion of

Franc dummy respectively. Although all the models except

Arabophones model specification shows a presence serial

correlation but the F-statistic entailed that all the model

specification are good. That is, one can make inferences from the

result because the F-statistic is significant. In addition, the

R-squared and the Wald test shows that the model fitness was good

as well as the null hypothesis of overestimation were rejected in

the entire models. All the estimations were carried out under

fixed effect specification of unbalanced panel data suggested by

the Hausman test.

The result showed that the contemporaneous Financial

Development (FD), Domestic Savings (DS), Balance of Payment

(BOP), Trade Openness (OPN), lead of Domestic Investment (DI),

lead of Domestic Savings (DS) and lead of Infrastructure

Development (INFRD) are determinants of Foreign Direct Investment

(FDI) inflows in Arabophones countries that were statistically

significant. The same variables were identified as some

determinants of FDI inflows in Francophones countries except the

lead of Domestic Investment (DI), the lead of Domestic Savings

(DS), and lead of Infrastructure Development (INFRD) and

inclusion of lagged INFRD and inclusion contemporaneous INFRD and

DI were also statistically significant. The non-landlocked Africa

countries model showed that the same variables were also the

determinants of FDI inflows inclusive of contemporaneous Real

Economic growth (EG), contemporaneous DS, contemporaneous

Inflation (INF) and excluding their lagged and lead variables.

There was a slight change when Linguistic approach differences

were captured as dummy variables. Although, the dummies were not

statistical significant but it improves the model by the

identifying lead OPN as one of the determinants of FDI inflows in

non- Landlocked countries of Africa.

According to the result, an increase in the financial

development by a unit increases the FDI inflows to Arabophones

countries by 0.0003 units, in the non-landlocked by the same

units but reduces the FDI inflows to Francophone countries by

0.001 units. The effect was statistically significant. The result

is consistent with Hermes and Lensink (2003) and Nabamita and

Sanjukta (2008), which found a positive relationship between

financial development and foreign direct investment. However, the

negative effect with the Francophones countries can be associated

with the type of foreign direct investor"s motive.

Furthermore, an increase in infrastructure development

(INFRD) reduces the FDI inflows to Francophones countries by

0.0003 units and the effect is statistically significant.

Although the effect in both Arabophones and non-landlocked

countries have a positive effect but was not statistically

significant. Good infrastructures stimulate production, reduce

operating costs and invariably encourage FDI inflows (Wheeler

& Mody, 1992). It also increases the productivity of

investment and hence economic development. But this finding were

not consistent with the relationship between INFRD and FDI for

Francophones countries and that of Arabophones in the long-run.

According to the current paper's findings, an increase in INFRD

by a unit reduces FDI inflow to Francophones by 0.0003 units and

0.0008 units to Arabophones in the long-run.

There was a positive relationship between the domestic

investment (DI) and FDI inflows to Arabophones and Francophones

countries. This implies that FDI inflows crowd in DI in both

countries, and its effect on Francophones is statistically

significant while on Arabophones is not. However, domestic

investment has a positive effect on FDI inflows to Arabophones in

the long-run and statistically significant at 10 percent as

depicted from the empirical result.

Fiscal and monetary disciplines by the recipients"

government have a negative effect on the FDI inflows in their

country. These disciplines can be seen from the nature of their

balance of payment (BOP). The empirical findings in this paper

showed that an increase in BOP by a unit reduces the FDI inflows

by 0.0006 units, 0.001 units, and 0.0009 units in Arabophones,

Francophones and Non-landlocked Africa countries excluding

Lusophone countries of Africa respectively.

Another determinant of FDI inflows to Arabophones and

Francophones countries was trade openness. In theory, trade

openness effect on FDI inflows to an economy depends on the

investor"s motivation for engaging in FDI activities (Brainard,

1997; Markusen and Maskus, 2002; Navaretti and Venables, 2004).

According to the authors, a more open an economy becomes the

better for non-market seeking investors who would like to use the

destination as an export base. On the contrary, market seeking

investor whose target market is the host countries would prefer

less openness. This paper result to a certain extent is

consistent with the theory based on the non-market foreign direct

investor"s motive, that is, an increase in the trade openness

(OPN) by a unit increases the FDI inflows to Arabophones

countries 0.0412 units and to Francophones countries by

approximately the same units (0.0411 units). It also increases

the FDI inflows to Non-landlocked countries of Africa excluding

Lusophone countries by 0.0266 units and to the model that

captured the Linguistic differences as dummies in the short-run

by 0.030 units.

Contemporaneous inflation (INF), real economic growth

(EG) and domestic savings (DS) have a positive effect on FDI

inflows to Arabophones, Francophones and Non-landlocked excluding

Lusophone countries and the models with dummies. Although, the

positive effect is statistically significant on the other models

excluding Arabophones and Francophones models, the DS has a

negative effect on FDI inflows to Arabophones countries. That is

a percent increase of DS reduces FDI inflows to Arabophones

countries by 0.0004 units in the long run.

Página siguiente  |